History of enteral nutrition and its influences on mankind – or, a picnic in space

The beginning of enteral nutrition is directly connected to the development of nutrition tubes, and their roots reach back into antiquity. People have been exploring the theme of undernutrition and malnourishment since the time of ancient civilizations in Egypt, India, Persia, and China.

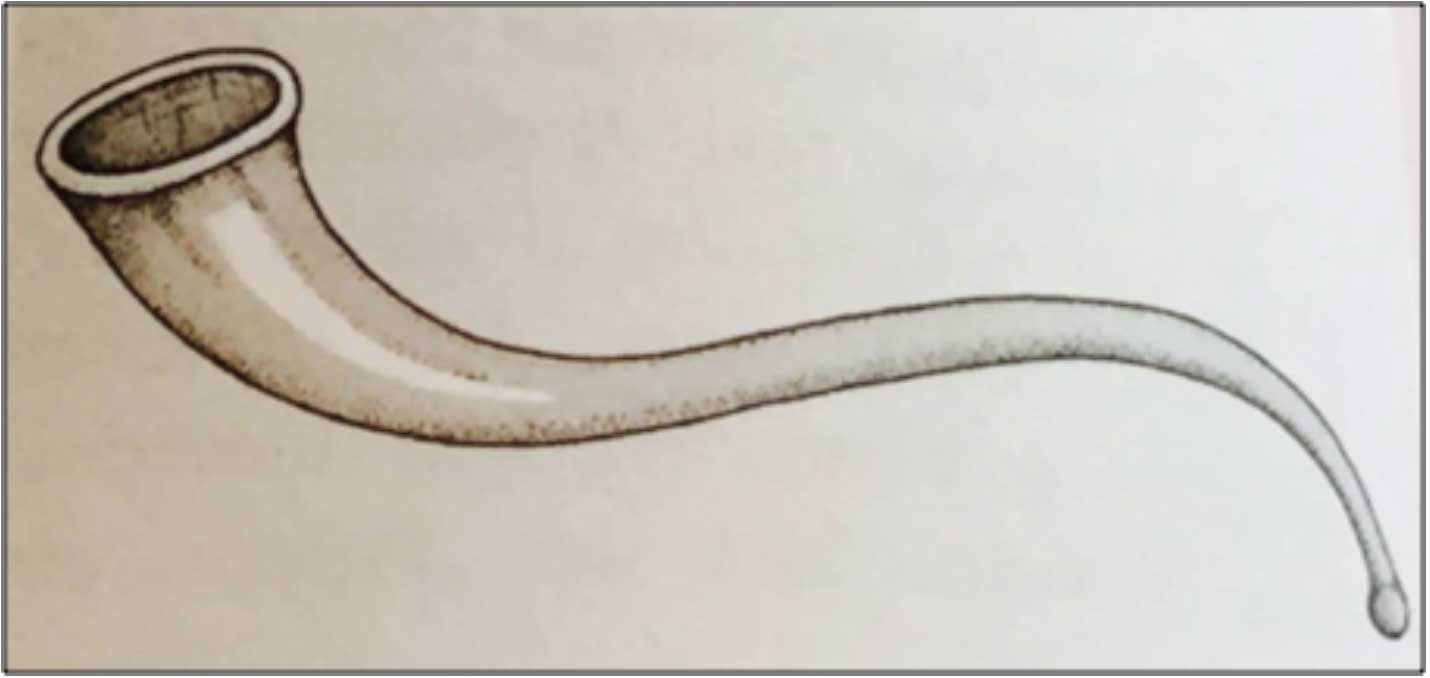

Initially, nutrient enemas were administered to people in order to assure an optimal nutritional intake. The nutrition (usually a mixture of pureed and liquid foods containing broths, sheep’s milk, buttermilk, barley gruel, etc.) remained in the rectum for several hours with the hope that it would be absorbed. It was not until the 12th Century that the belief that nutrition was absorbed in the rectum changed. Avenzoar, a Spanish born Arab doctor considered the stomach to be the only location where nutrition absorption could possibly happen. Patients who were unable to swallow would be fed through their mouth with a silver, funnel-shaped cylinder (figure 1). Avenzoar could not anticipate it, but his technique would be implemented for another four hundred years.

Figure 1 (Kalde S, Vogt M, Kolbig N, editors. Enterale Ernährung. 3. ed. München: Urban & Fischer; 2002.

The apparatus changed in the 16th Century as scientists explored how to optimize the original nutrition feeding tube. In the 17th Century, the first throat and stomach tubes were used, and nutrition was artificially fed into the mouth with a large syringe (figure 2). In that era, these procedures were revolutionary. For the first time, it became easier to artificially deliver food into the mouth. But, science did not rest, and so by the end of the 18th Century, they had succeeded in employing the earliest version of a stomach pump. The first electric stomach pumps came into use in 1930.

Figure 2 (Kalde S, Vogt M, Kolbig N, editors. Enterale Ernährung. 3. ed. München: Urban & Fischer; 2002.)

The delivery of nutrition through the intestine was also successful for the first time during the 19th Century, and modern day jejunal feeding tubes have their origin in this early method. A case study from over 170 years ago describes a woman whose life was saved using this technique. She had been impaled by a steer and could only be fed through a jejunal opening. In 1878, the French surgeon, Surmay, described the technique of jejunostomy. The procedure would be further improved upon in the years following his innovation.

During the 20th Century, feeding tubes were successfully produced out of a variety of materials (such as leather, rubber, silicone, and polyurethane). Gross and Einhorn implemented the first duodenal feeding tube in 1909. This technique was improved a little over a decade later, to allow the duodenal feeding tube to be laid through either the mouth or the nose. This so-called transnasal feeding tube made long-term feeding tubes possible for the first time.

In times of war, it became particularly important to provide nutrition to patients with jaw injuries and swallowing issues through a feeding tube (figure 3), as the number of patients requiring this type of intervention increased.

“It was a small step for Neil Armstrong but a giant leap for mankind.” The exploration of space in the 50’s and 60’s caused a boom in the arena of astronaut nutrition. As time went on, the flavor was improved and ingredients and methods of production were replaced by substantially cheaper alternatives, and this had a profound effect on the simultaneous development and improvement of enteral nutrition. Today, there are innumerable varieties of balanced nutrition formulas on the market. This does not always make it easy to determine which one is the optimal version. In every country, there is a broad assortment of products. Furthermore, every child tolerates each of these nutritional formulas differently. Which balanced formula to choose, or whether home blenderized tube feeding is the better option, is a more relevant question than ever.

The first PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) tube was successfully placed in the 1980’s. The PEG’s inventors, Gauderer and Ponsky, were the first to succeed in placing a feeding tube that directly accessed the stomach with a minimally invasive technique.

Optimization and innovation in methods of delivering enteral nutrition are still happening today. Recently developed advancements in medical science can be seen in the technology of percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) and the production of 2- and 3-lumen tubes.

If a child cannot, or should not swallow due to a medical condition, then they must be given nutrition through a feeding tube in order to ensure the best outcome. The feeding tube is a life-saving intervention. Once the child is medically stable, however, weaning from the enteral nutrition should be considered as soon as possible, especially as long-term tube feeding can cause many problematic side effects. Weaning is most successful with an interdisciplinary team. Read more about how to decide which tube weaning program is best for you here.

Your NoTube team!

References:

- Kalde S, Vogt M, Kolbig N, editors. Enterale Ernährung. 3. ed. München: Urban & Fischer; 2002.

- Gauderer MWL. Long-term gastric access: caveat medicus. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1996;44(3):356-8.

- Meyer EA. Einläufe für den Sonnenkönig. [Internet].2014 [cited 2015-02-11]. Available from: http://www.allgemeinarzt-online.de/a/1634112.

- Stein J, Dormann AJ. Sonden- und Applikationstechniken. In: Stein J, Jauch KW, editors. Praxishandbuch klinische Ernährung und Infusionstherapie. 2. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2003.

- Harkness L. The history of enteral nutrition therapy: from raw eggs and nasal tubes to purified amino acids and early postoperative jejunal delivery. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102(3):399-404.

- Vassilyadi F, Panteliadou AK, Panteliadis C. Hallmarks in the history of enteral and parenteral nutrition: from antiquity to the 20th century. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2013;28(2):209-17.

- Furst P, Stehle P. [Artificial nutrition--past, present, future]. Infusionstherapie (Basel, Switzerland). 1990;17(5):237-44.